A few months ago, roughly ten years after its release, I finally caught up with watching Irréversible. Infamous for it’s graphic depiction of violence and rape, it is a film with a Special Edition DVD cover proudly quoting Jonathan Ross that it “should not be missed”, but wisely omitting other descriptions suggesting it “might be the most homophobic movie ever made.”

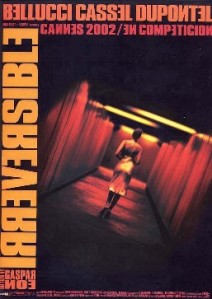

Irréversible is a French revenge movie, in which the rape of Alex (Monica Bellucci) prompts Marcus (Vincent Cassell) and Pierre (Albert Dupontel), her current and ex-lover respectively, to hunt down those responsible. A story told in the reverse style of Memento, where we witness the murder, the hunt, and then the rape, with the second half of the film showing us the relationship of the three protagonists earlier on in that fateful day.

However it is viewed, it is nearly always preceded by its reputation and the responses it garners are as extreme as the film itself, which left me feeling like my own may be somewhat alarming in its own right.

Basically, I was bored.

So what does this mean, and why am I writing about it? Does this mean that desensitisation of on-screen violence is inevitable? Are different members of society more susceptible to certain kinds of violence than others? Or more simply, am I just a broken human being? Allow me to explain…

For all its violence, Irréversible begins with a calm dualogue between two never to be seen again characters. Obviously designed to reflect on the film’s themes with the line “Le temps détruit tout” (“Time destroys everything”), French philosophy is something I have attempted to grapple with on previous occasions, but with little luck. After this we are shown Marcus and Pierre to be bashed, broken, and surrounded by police upon leaving the “Rectum”, a gay S&M nightclub. A scene which quickly shifts back into the prolonged sequence in which they continually ask what seems to be every patron if they are “Le Tenia”, or “The Tapeworm”.

This right here is the first problem. The subtleties of philosophy aside, the film’s opening is just so tenuous. The search for Le Tenia is just too long, arduous, dark, accompanied by the most mind numbing drone, long, and repetitive that by the time Le Tenia is found, the caving in of a man’s skull by fire extinguisher, more brutal than even the film’s choice of names, only left me thinking ‘Ooh, that’s clever, I wonder how the film-makers achieved that.’ After the chase to find the club (this time with prejudice against race and transsexuals joining that against homosexuality, but at least there is more diversity of action to keep your interest), we finally meet Alex, who now we have known her for all of two minutes, suffers the vicious attack we have just witnessed the vengeance of.

And like the unknown but specifically placed extra in the background, I too just felt like walking away. Not because of fear, or disgust and horror which I’m sure spurred many other viewers, but, as I mentioned before, because I was bored.

Whilst briefly searching (unsuccessfully) for the Guardian quote describing it as “A Masterpiece” (again from the DVD case) I found only reviews that described the overall film as nothing worthwhile, but still described the pivotal event of Alex being “unwatchably raped.” Yes, the act itself is undeniably savage, but I just fail to see how the way it’s presented by Irréversible has that effect.

Irréversible is a cinematic feature film. A motion picture, in which the notorious sequence at the epicentre of the whole film, essentially has no motion. Lack of editing aside (each scene is a single continuous take) the entire rape, in which Alex is pinned to the floor and endures the most basic of thrusts, is shown from one single, unmoving view point. I have no doubt that the filmmakers’ intentions were to confront you with its brutality in an attempt to illicit both shock and empathy, the unflinching camera forcing you to helplessly suffer, mirroring the very invasion that Le Tenia is committing.

And that’s not to say I don’t find any depiction boring. It is far from the only film to depict such an act, although perhaps the most comparable is the just as self-assertive Baise-Moi, another French offering in which it is the victims themselves who take their revenge on any men they can lure. Released two years prior, the film with two female co-directors depicts rape in the only way which can do the horror of actual rape any justice, realistically. Baise-Moi, whose title literally translates to “Fuck Me” combines images of violence, blood, and unsimulated sex in a graphic depiction that I amongst many others found shocking, because it comes across as taking the idea of rape seriously, not as a gimmick.

Admittedly unsimulated sex onscreen is not for everyone (it has lead to many countries naively classifying it as pornography), but when you consider that Irréversible features only the threat of accompanying violence, and that both Alex and her assailant are as fully clothed as possible throughout to the extent that the only “nudity” is obviously CGI, it made me wonder why a film so seemingly out to shock (an effect I believe any film trying to explore such ideas should try to achieve) wouldn’t try to follow at least some of its predecessor’s example.

Again, not that sheer brutishness is needed in order to achieve this shock, as shown by the unexpected events in the office of Män som hatar kvinnor; The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo to you and me, but known as “Men Who Hate Women” in the original Swedish. Surprise should never be underestimated, but is something the film-makers decided to exclude through the inherent nature of a well publicised, narratively backwards rape-revenge flick.

Two different approaches from two different films in which rape is treated in as serious a way as it should be. To me, Irréversible doesn’t, resulting in me watching a ‘rape’ which made my eyes leave the screen out of boredom, not disgust.

But I have to admit the film itself is only half of the equation, myself being the other. Although I have finished both my university courses and am no longer registered at any institution, it is fair to say that I will always be a student of film. More than just my own appreciation of the medium, I have spent years of my life being formally trained to analyse it, and to pick it apart like a watchmaker in order to see what makes each specimen tick. This is something which I cannot unlearn. That is not to say that I can no longer be swept away into the world presented on-screen before me, but I am now not just more aware of how I am being swept, but importantly, much more critical when I’m not.

The tedium of the initial search through the club was all this film needed to take me out of its world (if I was ever there to begin with), and make me all too consciously aware that what I was watching, fictional characters within a fictional scenario, just wasn’t real. Additionally, in order to concentrate on its brashness, Irréversible had not taken the time to allow me to get to know, and consequently care for, its characters as individuals. I describe it not as rape but ‘rape’ (note the inverted commas) in the second to last paragraph because as far as I was concerned, I was only watching actress Monica Belluci, who was no more Alex than she was ‘that French girl’ in ‘those Matrix sequels’.

As someone for whom film plays an important part in my life, neither Irréversible nor Baise-moi were the first times I have seen such violence on screen. I watched A Clockwork Orange during my first year of university when discussing what my lecturer, Martin Barker, called the “Pornography of violence”; The idea that as audience members, perhaps worse than mere apathy, people enjoy watching violent acts depicted on screen. We may not like that we like it, but nonetheless, we (and more importantly, film-makers and distributors) recognise that we do indeed like it.

“We see a deadly sin on every street corner, in every home, and we tolerate it.” – Kevin Spacey in Se7en, David Fincher, 1995

Whilst there are many films that have merely jumped on the ‘violence for violence’s sake’ bandwagon, I have been able to sit through Saw films (the first three at least, from what I have heard the following sequels are all aboard said bandwagon) and unflinchingly find them fascinating. Where Irréversible presents only an animalistic reaction, and an opportunistic crime in which the rapist seems only mildly interested in getting back at the bourgeoisie, Saw is just one of many films which presents us with a philosophical idea through the use of stark visual images rather than novelty camera work and complicated language. Less mindless but more mindful violence, people being tortured in horrific scenarios of, essentially, their own making. We watch it to see people come face to face with a twisted karma, and have even found ourselves appreciating the logic for doing so.

Even when pulled into the world in front of me, and the (subconscious) knowledge that what I am seeing is not real, there is another element to consider. Unlike a close friend who avoids even James Bond films due to his experiences in the armed forces, throughout my own sheltered life I have never even witnessed an actual, horrific and violent act that I can relate the onscreen images to. Throughout my film watching life I have seen a number of things that have made other people scream, squirm, and look away, some of which I have even laughed at (although I hasten to add this is mainly due to low budget special effects, and the reactions of others). Until, that is, one lecture where we were shown a clip from a film that I unfortunately cannot remember. A simple clip in which someone, in close up, with no apparent prosthetics, takes hold of their thumbnail, and slowly peels it from their skin.

This sent shivers down my spine and put my teeth on edge, because it is a pain that I myself am personally aware of. It got to me because, unlike anything else I’ve watched, it is something I can relate to. Unlike rape and torture, it is something I know.

This is something which leads on to the last, and perhaps most important factor when considering my reactions to rape, both on-screen and actual. I am male. Even after learning of events that involve people I know, as well as personally being attacked on the high street of even my sleepy home town, I have never walked alone at night in fear of such an invasion of my personal privacy, purely because simple statistics tell me that I am more likely to commit rape than fall victim to it.

So why am I writing this? Certainly there are those who may see this post and my unsympathetic reaction to be controversial, and to those people I say don’t just move on, but that any and all comments are welcomed, and actively encouraged. If after pleading my case the verdict is am a broken human being, this is something I need to know about. But before making your decision, also consider this:

There is a notion I agree with, that attempting to defend callous actions with “the way she dressed showed she wanted/needed/deserved it” only degrades men, promoting the idea that we cannot control ourselves and that rape is something that should come naturally to me. This is a notion which I wholeheartedly disagree with. Yes, the human sex drive is a strong urge, but that is so for both men and women. As much as I consider a vow of celibacy to be a noble pursuit of many religions, I can’t be the only one to consider that suppressing things in such a way is one factor that lead to the scandals currently plaguing the Catholic Church (amongst others), but that does not mean that rapist is a natural state; regardless of the circumstances, it is a choice that people should be held accountable for.

But this is far from the be all and end all however, and I leave you with one final thought. I say this not in an attempt to alleviate any personal blame but to acknowledge what I believe is an unspoken contribution of my apathy towards Irréversible, and an issue that needs to be further addressed if we are to solve the wider problem that is making headline news in countries all over the world.

Whether through statistics, the rise in “women’s” services and charities, or the very nature of the antiquated and self-serving patriarchal world we are living in, there is an element of society which has taught me, as a male, that rape just isn’t my problem, and that I should tell jokes down the pub before I worry about it.